In the 1920s, the way the scenography system functioned was determined by new “aesthetic discoveries”. The immediate connection between stage design and the processes taking place in the realm of fine arts contributed to the introduction of avant-garde experiments focusing on cubist, cubofuturistic, and constructivist means of expression and their implementation in theatre. In a quest for forms that would be associated with the industrial era, Georgian avantgarde artists placed “passive reflection of reality” face to face with new methods of stage design. Following in the footsteps of European avant-garde painters, they decided to apply innovative principles of space planning. Georgian theatre underwent a process of transformation through bold avant-garde experiments, resulting in fundamental changes to traditional scenography principles, which was later followed by the repression and prosecution of Georgian painters and directors by Soviet authorities.

The process of reorganizing Georgian theatre is directly associated with Kote Marjanishvili (1872-1933) and Sandro Akhmeteli (1886-1937). At the beginning of the 1920s, after the introduction of Soviet rule, Georgian theatre found itself in the middle of a crisis. Marjanishvili, who had recently returned to his homeland having been invited to collaborate with Irakli Gamrekeli (1894-1943), and later at the newlyopened Kutaisi-Batumi theatre with Petre Otskheli (1907-1937), David Kakabadze (1889-1952), Elene Akhvlediani (1901-1975) and other artists. Painted decorations that had been created according to the rules of perspective and represented a specific acting environment were replaced by generalized spatial constructions, geometric forms and simultaneous stage installations, whose designs were based on the qualities of the surfaces. Georgian avant-garde artists awarded these multifunctional platforms the role of serving as the major components of stage compositions.

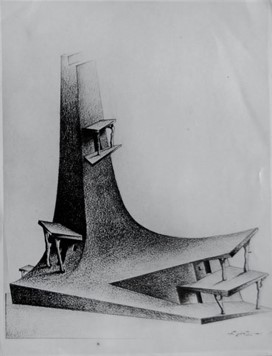

At the beginning of the 1920s, Irakli Gamrekeli produced scenery decorations for several plays of contemporary playwrights; among them Londa, A Mass Man (in cooperation with Kirill Zdanevich, 1892-1967) and Maelstrom. In the plays Londa and A Mass Man, the stage area was arranged with the application of spatial shapes and surfaces. The scenography was constructed based on colour spots, which were reduced to geometric symbols unrelated to any specific time or location. In Maelstrom, Londa’s minimalistic design was replaced with architectural details and multiple impressions (a collage of skyscrapers, cafes, dancers). The nominal machinery and stairs became necessary elements of a common decoration system, and were used for the creation of expressive and dynamic environments.

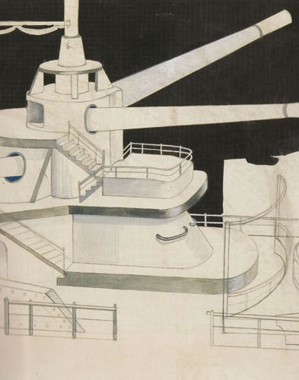

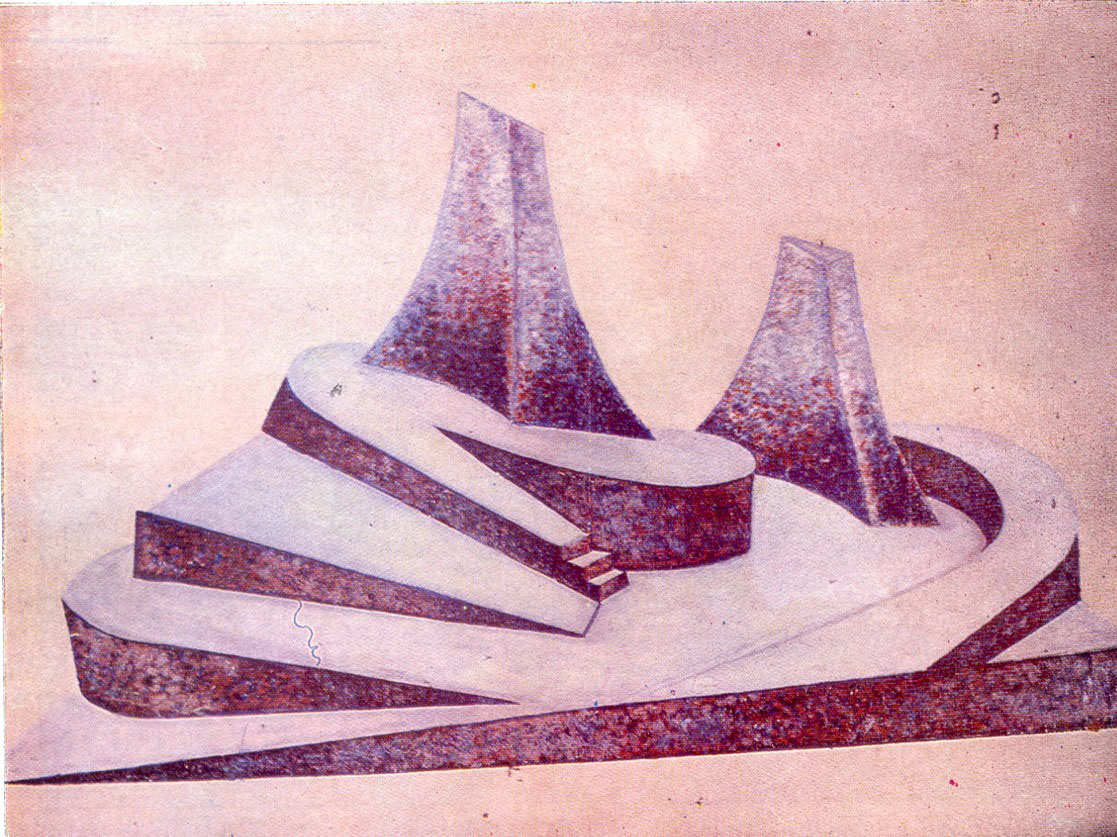

From 1926, Irakli Gamrekeli and Sandro Akhmeteli became involved in a process of very intense collaboration and launched their joint project of a theatre of “rhythm and pace”. Staging of the play Violation in 1925 already marked a shift in the director’s interest towards large scale action scenes, which would become one of the major features of his work. Events that took place in an interior were juxtaposed with effectual large-scale action scenes: a cosy family life repeated certain psychological details of actions that occurred on a battleship. Actors began to move rhythmically between the huge machinery, iron stairs, platforms and bridges. The decorations of the play Violation became a very interesting example of “constructivist design” on the Georgian stage. These scenography works of Irakli Gamrekeli were followed by other plays that were also created based on the principles of constructivism. A single shape produced by the painter as a decoration of V. Kirshon’s play The City of Winds enabled the viewers to enjoy the generalized image of an industrial city and united elements such as pipes, cisterns and different types of “interior”.

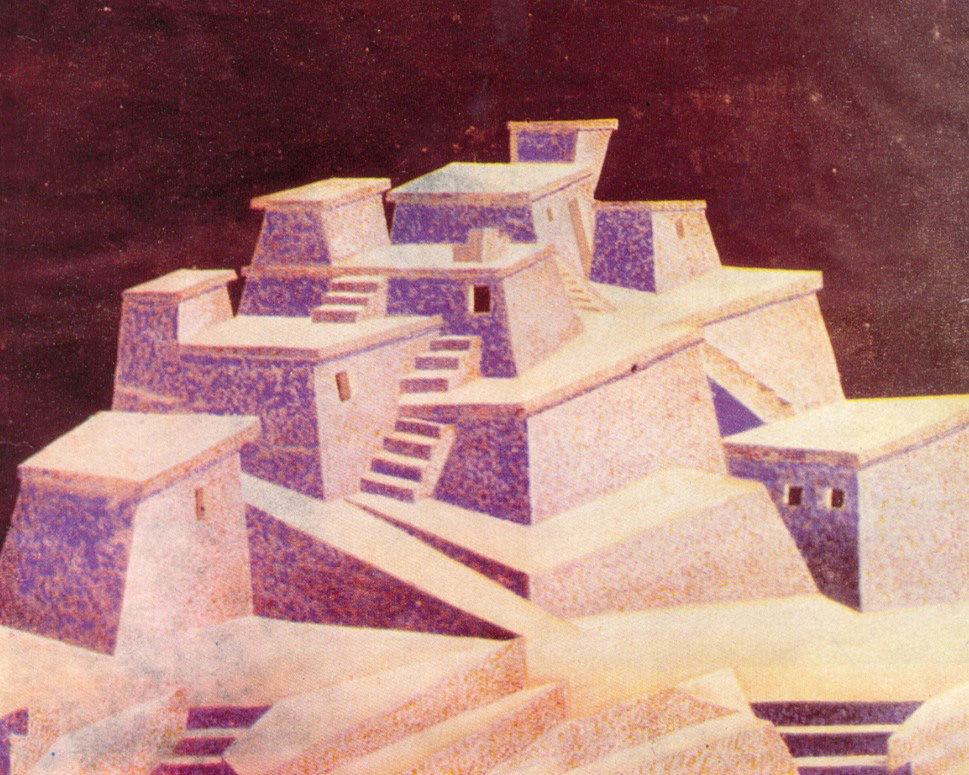

The highlights of the creative cooperation between the painter and the director were manifested in Anzori (1928) and Lamara (1930). Sandro Akhmeteli referred to Irakli Gamrekeli’s scenography as a piece of “architectural constructivism,” where the platforms spread out as tiers and the stairs represented a village. Like a living organism, “machinery that triggered associations” transformed itself in parallel with the action of the performers. In the play Lamara, the director used an entire system of squares and stairs to unfold action on several levels simultaneously. Along with decorations from Anzori, the play offered a very interesting synthesis of abstract forms and stylized elements of national architecture.

It should be noted that Soviet critics considered Maelstrom to represent a “negative influence” on socialist theatre. They attributed the avant-garde explorations of Georgian artists to formalism, and cited Irakli Gamrekeli’s “architectural constructivism” and Sandro Akhmeteli’s directorial style as the most important reasons for prosecution of the director, and subsequently launched a negative campaign against him. In addition, the Soviet authorities were concerned about the invitation the Rustaveli Theatre had received from the USA. Despite the huge success of Lamara, the director was requested to remove it from the repertoire. However, Akhmeteli declined the recommendation and was later accused of “nationalism”. He was dismissed from his post as artistic director of the Rustaveli Theatre, and several years later was accused of being involved in “harmful” activities directed towards the state, and staging a work by the emigrant writer Grigol Robakidze (1882-1962, Lamara). 1

Notwithstanding persecution and prohibitions, the innovative artistic methods of Irakli Gamrekeli, a scenographer inspired by avant-garde art, introduced the principles of “fine art directing” to Georgian theatre (along with Petre Otskheli, David Kakabadze and others). The processes described fundamentally changed Georgian avant-garde art, as well as the understanding of the role of painter/decorator that had prevailed at the beginning of the 20th century. Instead of being a mere passive illustrator of events, the scenographer was acknowledged as having collaborated with the director and was thus awarded an important function as co-author of the concept.

1. In 1937, in accordance with paragraph #58 of the Criminal Code of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Georgia, Alexandre (Sandro) Akhmeteli was sentenced to capital punishment and duly executed. His spouse Tamar Tsulukidze-Akhmeteli was imprisoned for ten years.

Author: Ketevan Shavgulidze

Source: atinati.com